Understanding the mechanism of how cisplatin and hearing loss are connected is the first step to developing cancer treatment plans that save patients’ hearing.

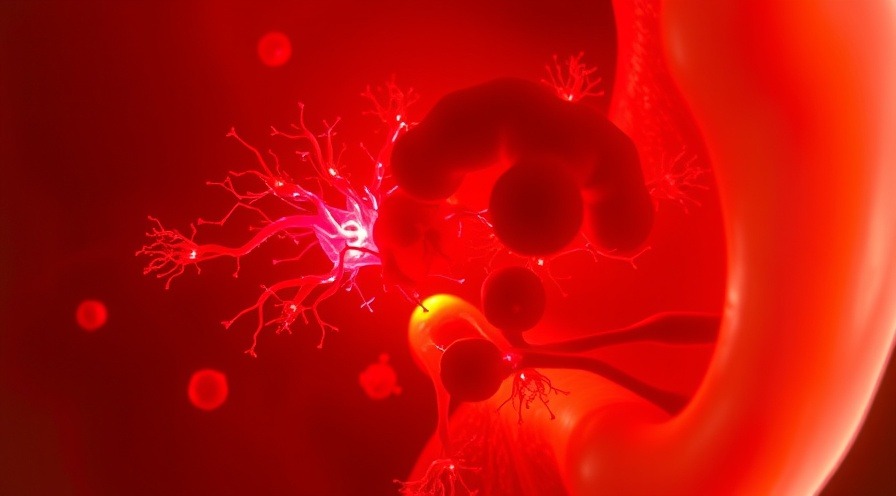

Pictured: Outer hair cells in an ear sample from a donor who suffered from cisplatin-induced ototoxicity, six hours after treating the sample with more cisplatin. The cells overproduced the protein APE2 (green), and the protein migrated directly to the mitochondria in the cell (red, overlaps with the green). Further research shows the APE2 protein damages the mitochondria in the outer hair cell, leading to cell death and hearing loss. Cell nuclei are blue.

Ever since cisplatin was introduced as a treatment in the 1970s, physicians like Jianjun Zhao, MD, PhD, have seen a disturbing pattern. Even with the rise of immunotherapy, chemotherapy agents like cisplatin remain first-line treatments and were highly effective against testicular, ovarian, bladder, and other cancers. However, patients were inexplicably left with severe side effects including permanent hearing loss and tinnitus. Recently, Dr. Zhao and his team discovered a mechanism that explains the link between cisplatin and hearing loss.

Their study, published in Cancer Research Communications, reports that cisplatin causes inappropriate gene activation and protein interactions that lead to cell death in our outer ears.

“These mechanisms totally change how we think about the concept of drug toxicity during cancer treatments,” Dr. Zhao says. “It is often assumed that cisplatin and other cancer treatments cause organ damage through the same mechanisms by which they target tumors. We’re showing that the drug can indirectly cause normal organ damage by deregulating our genes. That type of toxicity is much more treatable, and preventable.”

Dr. Zhao and the study’s co-corresponding author, Jianhong Lin, MD, PhD, both saw the permanent side effects from cisplatin chemotherapy in the clinic. Many of their patients were children who experienced side effects even in the remission stage. Hearing loss in childhood can impair speech and language development, leading to additional social challenges and increased financial burdens for families, Dr. Lin says.

“Before, it was harder to prolong survival for cancer patients, so nobody had room to worry about long-term side effects. They were just trying to keep their patients alive,” she says. “Now, we have treatments that can prolong survival and even cure cancer. So, we need to think more about the side effects and how to prevent them to preserve the quality of the lives we save.”

Protein interactions in inner ear cells cause the link between cisplatin and hearing loss

The team analyzed ear samples from healthy donors and from donors who experienced cisplatin-related hearing loss. They also studied preclinical models of cisplatin-induced ototoxicity in the lab. Previous studies found high amounts of cisplatin had accumulated in the ears of donors who suffered from ototoxicity. This accumulation caused some physical damage to the ear, but not enough to explain the high rates of irreversible hearing loss and tinnitus.

Analyzing the outer hair cells of the inner ear (small hairs necessary for hearing) showed that the cisplatin had upregulated, or “turned on,” a gene that encodes a protein called APE2. This upregulation led to elevated levels of the APE2 protein in the outer hair cells, which had more protein than they needed.

In healthy cells, APE2 repairs DNA damage in critical cellular structures called mitochondria. When there is more APE2 than there is DNA damage to fix, the excess protein can act in ways it would otherwise be “too busy” fixing DNA to act. Drs. Zhao and Lin showed that the excess APE2 interacted with a protein unique to the inner ear and the kidney called non-muscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMHC-IIA) encoded by the MYH9 gene. This abnormal interaction prevented the mitochondria in the outer hair cells to stop working properly. Without the “powerhouse of the cell,” the outer hair cells died.

The Zhao Lab is developing treatments that prevent cisplatin from dysregulating APE2, with the long-term goal of preserving patient health and enabling providers to prescribe higher levels of cisplatin to treat stronger cancers. They have a therapy that is currently pending patent approval, and are working with Cleveland Clinic Innovations to fine-tune the therapy in preparation for preclinical and potential clinical trials. Their work affects more than the ear; previously the team demonstrated that cisplatin causes kidney damage during chemotherapy, a process also involving APE2. The Zhao Lab is performing many other studies, both published and under review, investigating side effects of cancer treatments including radiation toxicity in the brain and chemotherapy toxicity in the heart.

“No one ever truly knows who will get cancer, or when, or what kind, or why,” says Dr. Lin. “Our primary goal in improving available cancer treatments is to deliver solutions that reach the clinic, addressing life-threatening side effects and ultimately helping as many people as possible to improve their quality of life throughout survivorship.”

Add Row

Add Row  Add

Add

Write A Comment